A diverse clade, Palinanthropi are united through not only being obligate air breathers, but also through having their three gill arches return to being a larynx, a neo-larynx, for the regulation of air flow and for the production of sound to communicate with conspecifics. On top of their retention of mammary organs to nurse their dependent offspring, they regained endothermy from the poikilothermic concestor of all Anthropomundan posthumans, making them among the most still-mammalian of them. Above all, having lost the tail from M. progenitor days, they are the most human of all of them, if secondarily so.

Two major clades diverge from the palinanthropid cenancestor: Phocacetanthropi, raptorial carnivores; and Chungi, thick-skinned, grazing herbivores. Species within both subclades are often gregarious, forming pods of around a dozen or so individuals. Basally, both subclades possess phocapod, or seal-like, feet, which have thickened into fish-like plectropod feet in phocacetanthropids.

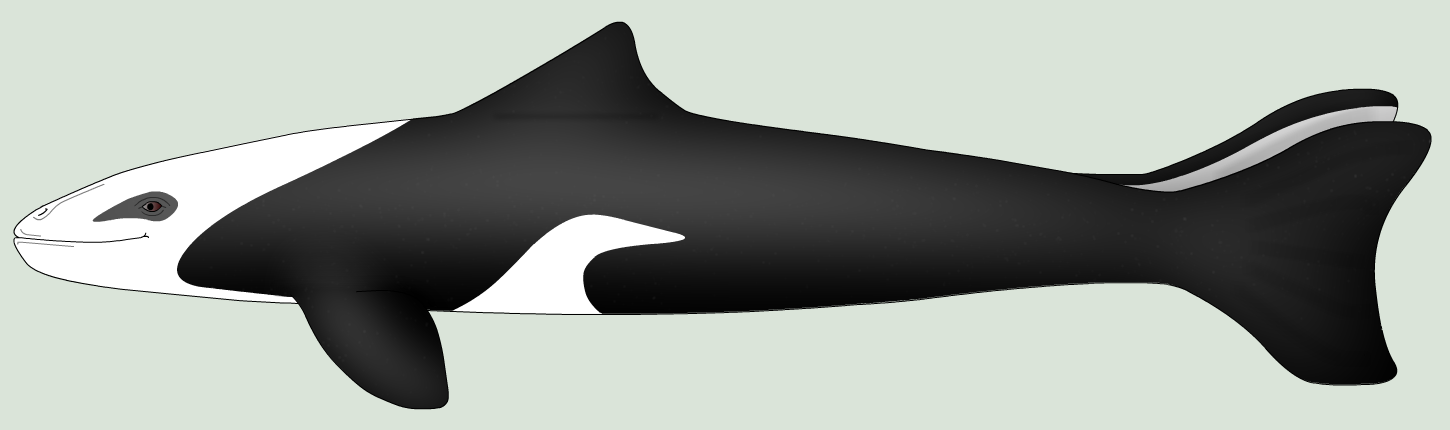

The killer werewhale is one of the most prolific predators of Anthropomundus's oceans. Its usual prey are small-to-medium sized posthumans, though, in the family units it forms, it can take on much larger quarry, such as the various species of large filter-feeding werewhales that trawl the seas with their expansive mouths, or isolate their young. Killer werewhale families search for food along the coasts or pursue it in the open ocean, communicating to each other with grunts and song.

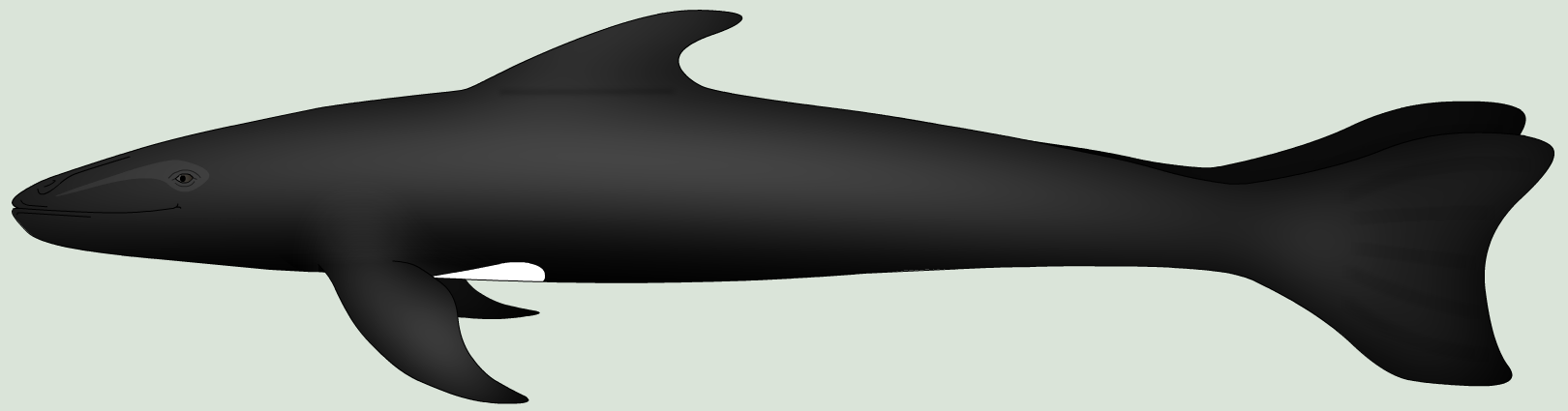

Though far from the only sharply black-and-white posthumans on the planet, their coloration nevertheless will confuse unsuspecting prey much as it does in its much larger, browner cousin, the killer werewhale (Hominorca necator), in the shallow waters and kelp forests they regularly patrol in its range. They live in family units of about a dozen individuals.

As one of the fastest marine posthumans on Anthropomundus, the blackfish shares similar adaptations as the pilot whale, such as thin, sickle-shaped pectoral flippers that, combined with a narrower body shape and a flattened, curved dorsal fin allow it to catch up to swift prey in the twilight zone, which is its primary hunting territory.

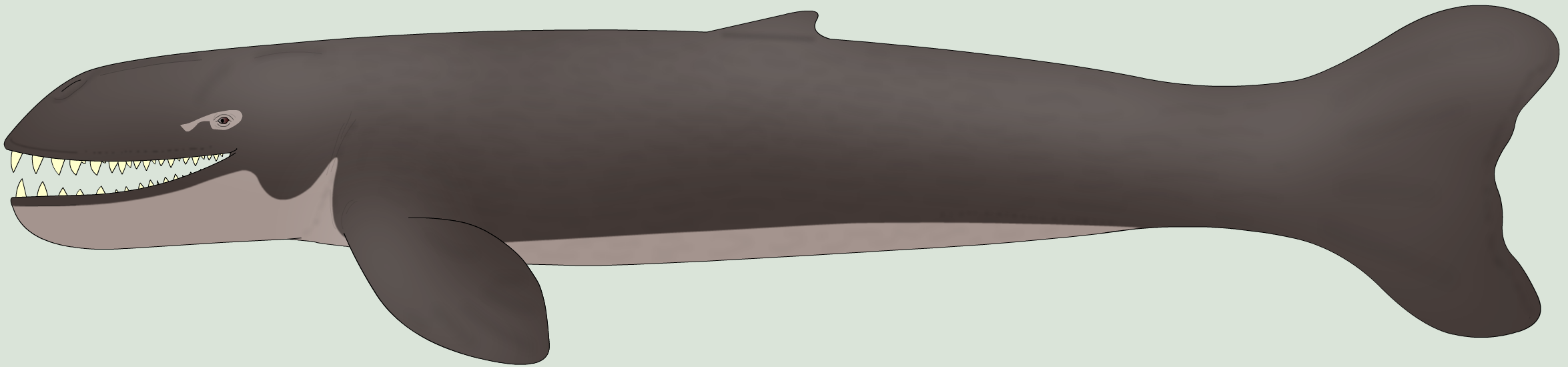

Livyadam is the most massive and the second longest predator on Anthropomundus, surpassed only by the grand grampus (Anthrocetarchus paraleviathan), a raptorial cetoid posthuman measuring at 22 m, with which it competes ecologically. It utilizes large jaws lined with thick, sharp, deeply rooted teeth to take big, bloody, blubbery bites out of the large filter-feeding posthumans that dominate the oceans, or at least snag smaller ones, including the offspring of the former. Unlike most phococetanthropids, this behemoth lives solitarily, whose only social interactions include butting heads among males, rumbling, guttural musical courtship, mating, and between mother and offspring. The relative abundance of its prey as well as its great size is a fact aided by how rare this monster is; it produces only one offspring and mates highly intermittently. The equivalent of a large-scale whaling operation from Earth would render this species extinct in a decade's time.

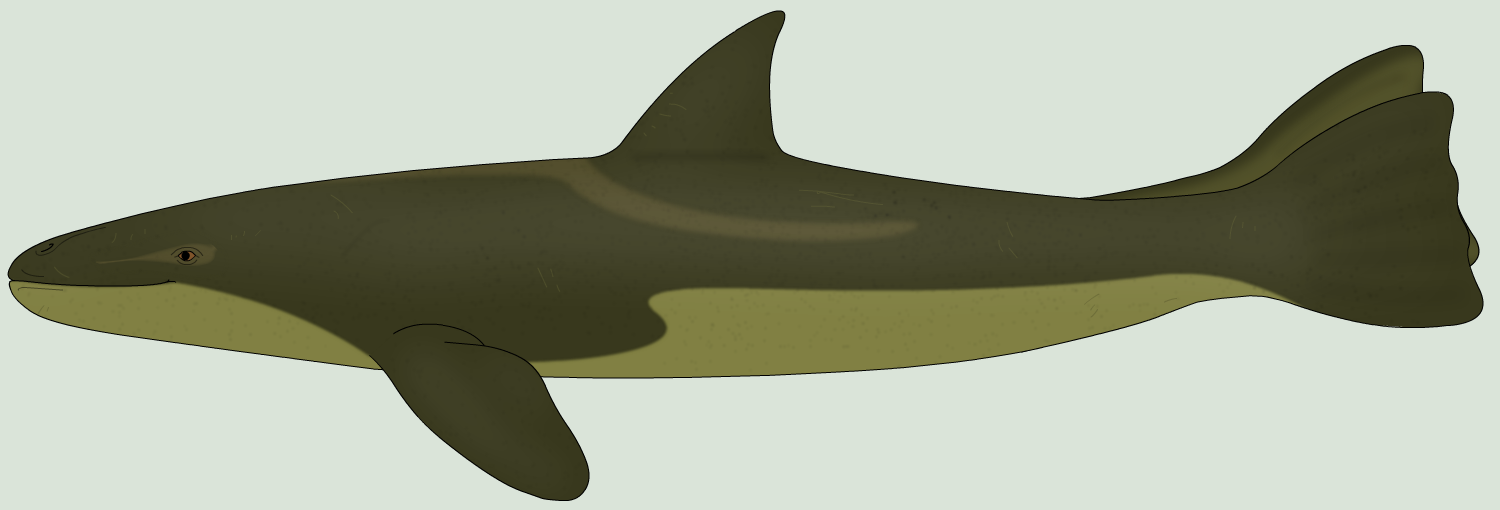

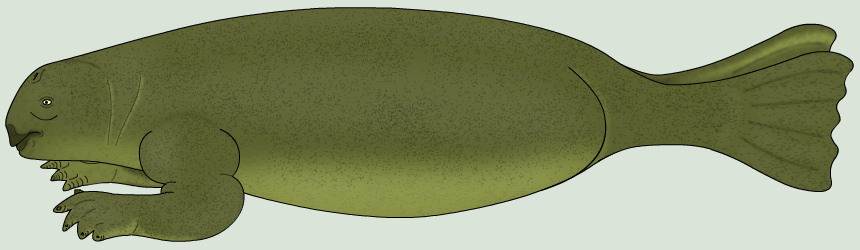

The humongous chungus is one of the largest true herbivores on Anthropomundus, it dwarves even the three-meter big chungus (Chungus marinus) and its relatives, but is eclipsed by the stellar chungus (Hydronatalis gigas) at ten meters and is outright dominated by the island-like kanaka moku (Kanakamoku iliomaomao) at fourteen meters. It is often found in pods of around five to ten, traveling between beds of algae and kelp forests. Even despite its profound defenses in the form of their immense size and thick skin, it and its pod must keep a move on, or the smaller and weaker among the pod risk falling prey to posthuman predators that strategically frequent these sites for their quarry, like killer werewhales.

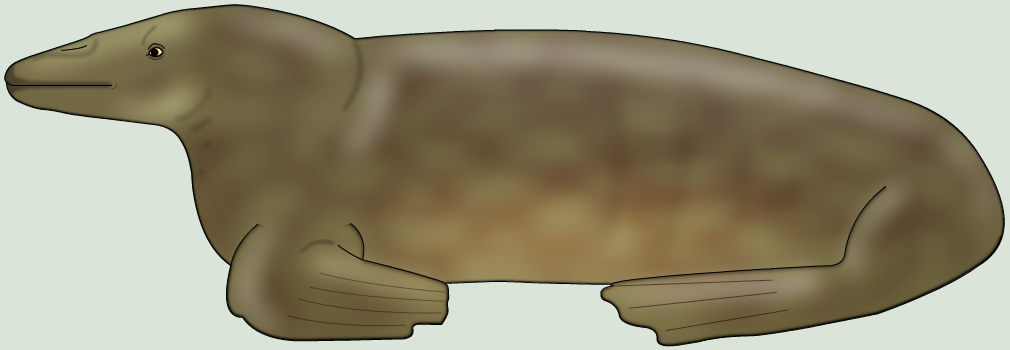

The mottled meal, along with the rest of Phocanthropi, represents humankind's first steps back on dry land on Anthropomundus. Having diverged from a common ancestor with Phocacetanthropi, their ability to breathe air enabled them to clamber onto the beaches and rocky cliffs of Anthropomundus, helping them to evade the predators of the ocean and allowing them to find a safe place to mate and raise offspring. Still, there will be predators that follow them onto land... and even now, as some species of phocacetanthropids learned to safely beach themselves to catch them in the manner of an orca beaching itself to catch seals on Earth.