Cetanthropichthyes are among the most post-human of all Anthropomundan posthumans. They are even among the most post-mammalian of all Anthropomundus. While fertilization and gestation remain internal, the multiple offspring are precocious right out of the womb, no nursing needed (with the accompanying loss of mammary organs) aside from the first meal of the afterbirth. They moreover have lost the lungs, even as a bellows for facilitating branchial respiration―save for alveolar structures diverging from the bronchi that serve as gas bladders―and breathe by facilitating a flow of water over their gills, through the mouth or through the nostrils. Above all, their gill arches possess rakers, which, like in bony fish back on Earth, can assist in a multitude of feeding functions from filtering plankton to cutting up larger prey. Lastly, they have completely lost their hind limbs, and are propelled exclusively through a fluked, cetacean-like tail derived from the artificially reimplemented, embryonic one of M. progenitor.

The cetanthropichthyans occupy a certain range of ecological niches. On one hand, the ubiquitous manchovies filter the diverse phytoplankton, from the indigenous purple to the imported green, with feathery gill rakers. On the other, though, some forms have those rakers like the teeth they may still retain in their mandibles and maxillae. These would make them formidable predators, allowing them to compete with the predators of the more basal jaw types in all of the oceans of Anthropomundus. Moreover, one lineage has taken evolutionary advantage of the ossified nasal cartilages otherwise flattened against the face, projecting them out pointily, fortified with hardened, sharp keratin and more bone.

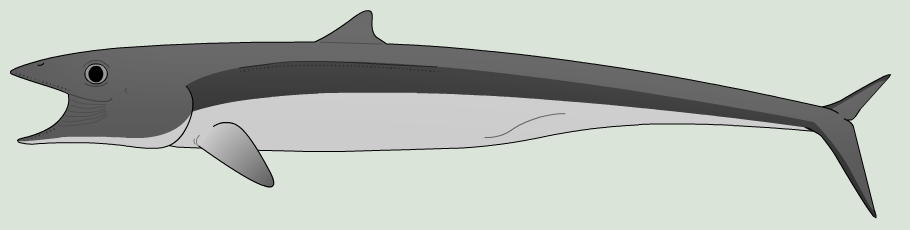

One of many species of small, pelagic filter feeders called manchovies, the blackstripe forms massive schools like those of their fishy Terran namesakes, opening the mouth wide as its near-microscopic, planktonic posthuman relatives and ocean detritus fall into fine, feathery gill raker nets before they are scraped off by the tongue and swallowed. This species also has the capacity to form bait balls as a desperate maneuver to protect as many of a shoal's members as possible as it is ganged up on by the individuals of numerous species of posthuman predators patrolling the ocean―and some of the air, too.

It gives birth to dozens of tiny offspring, with due female shoal members separating out to form a proximal, detachment "maternity shoals" to ensure not only physical safety from other adults but also food security for their offspring, who are fed not of milk but of falls of of phytoplankton directly into their fully developed gill raker nets—after their first meal of afterbirth. After giving birth, each mother swiftly returns to their shoal as their progeny go off to form their mini-shoals away from their parental ones, and closer to the surface to maximize phytoplanktonic intake. Few survive into adulthood, with those that do going on to joining an adult shoal, identifying the species by their lateral black marks.

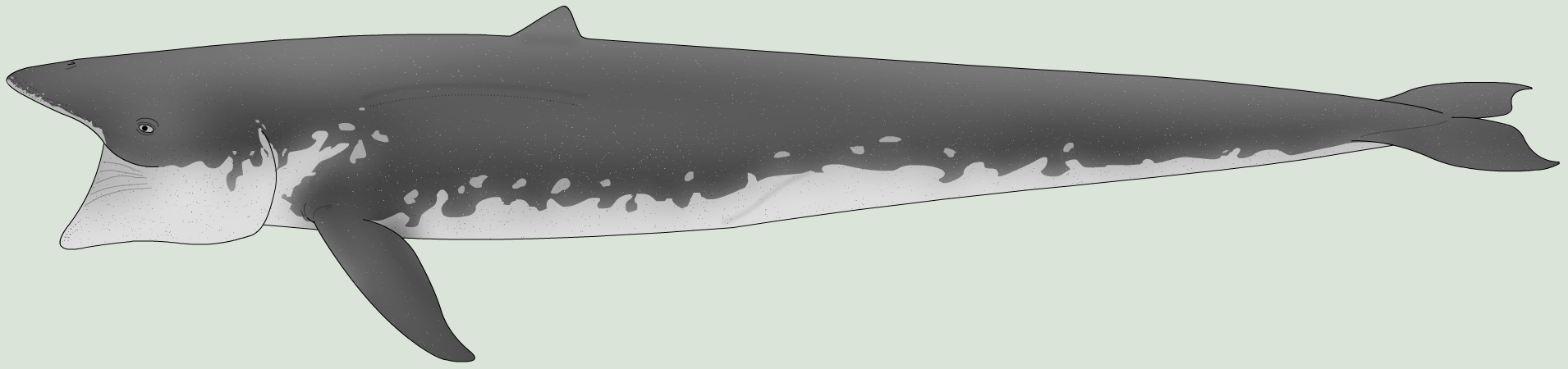

The megamouth manchovy is a large, cold-blooded filter feeder that targets shoals of planktonic posthumans, trapping them with baleen-like gill rakers, inflating pleated cheeks and soft, fleshy opercula as it plows through agape for its comparatively tiny relatives. The third largest of the manchovies, it primarily swims in the lower epipelagic zone, leaving the middle and upper epipelagic zones for the mega manchovy (Megalanthropengraulis megista)—the largest manchovy species—and the baskerman (Orphninocetanthropus epipolaeus), respectively. It gives birth to two or three (sometimes four) precocious offspring at a time.

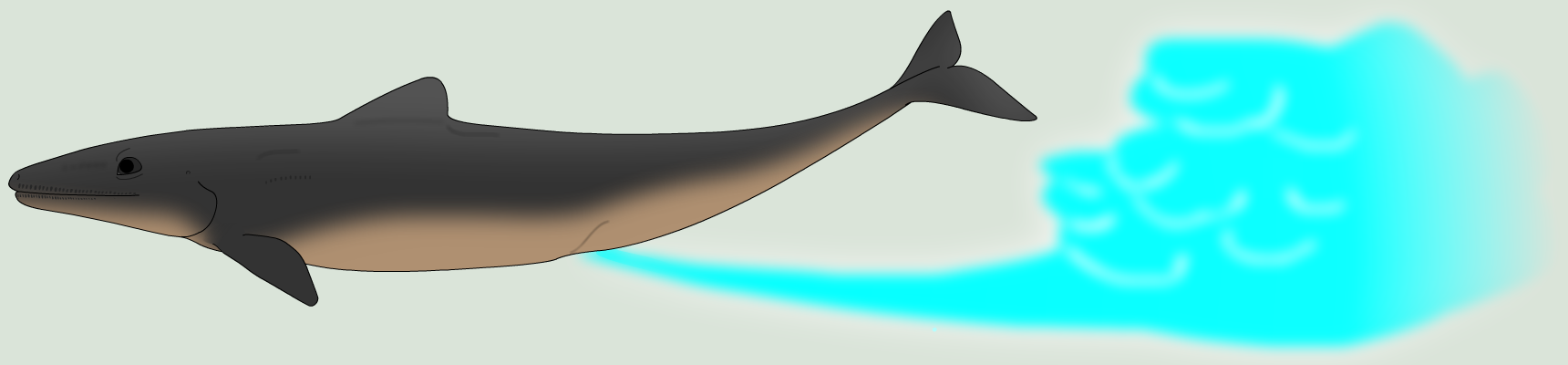

The glowsquirt earns its name by a peculiar defense mechanism it unleashes on eager predators: an effusion of glowing enteric flora from its gut, termed photodiarrhea, kicked into into their faces by means of the fluke, endangering them by making them visible to other posthuman predators of deep. This flora is stored in twin outpocketings of the rectum adjacent to the anal canal, fed by passing fecal matter and released in a sudden, nervous jolt. Outside of this spectacular sphincteric feat, their lives are fairly ordinary for deep sea posthumans, feeding on their smaller, often planktonic posthuman relatives.

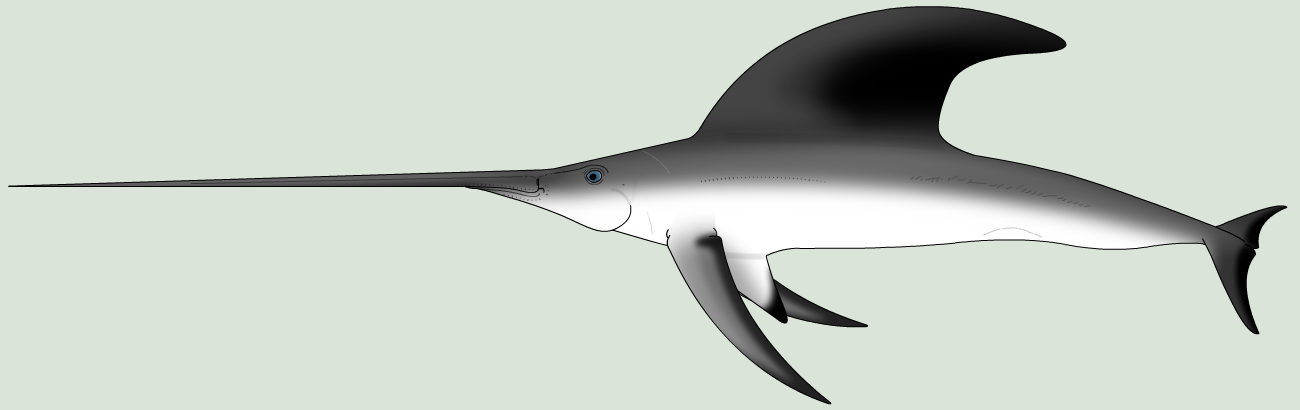

Echoing the sharpened istiophoriforms of old Earth, we have the fastest posthuman species alive in the blue Anthropomundan oceans: the sail person. As one of the gladiinasids, it utilizes its highly streamlined shape stabilized by a very large dorsal fin and even a novel sternal fin, propped up by a projection of the sternum and the xiphoid process (and not the one on the creature's face, as it were). With excellent eyesight, when it spots a bait ball of its favored manchovy cousins, it charges in, thrashing its nose-sword side-to-side using what remains of the neck muscles and their bodies to slash, stun, or impale the hapless shoalers, before sucking their injured prey into their mouths, shredded by razor-sharp gill rakers as they are swallowed. The sail person is parenthetically as truly vicious as other posthuman species elsewhere in the Milky Way that could be called "sail people", with the only difference being what part is considered a "sail."

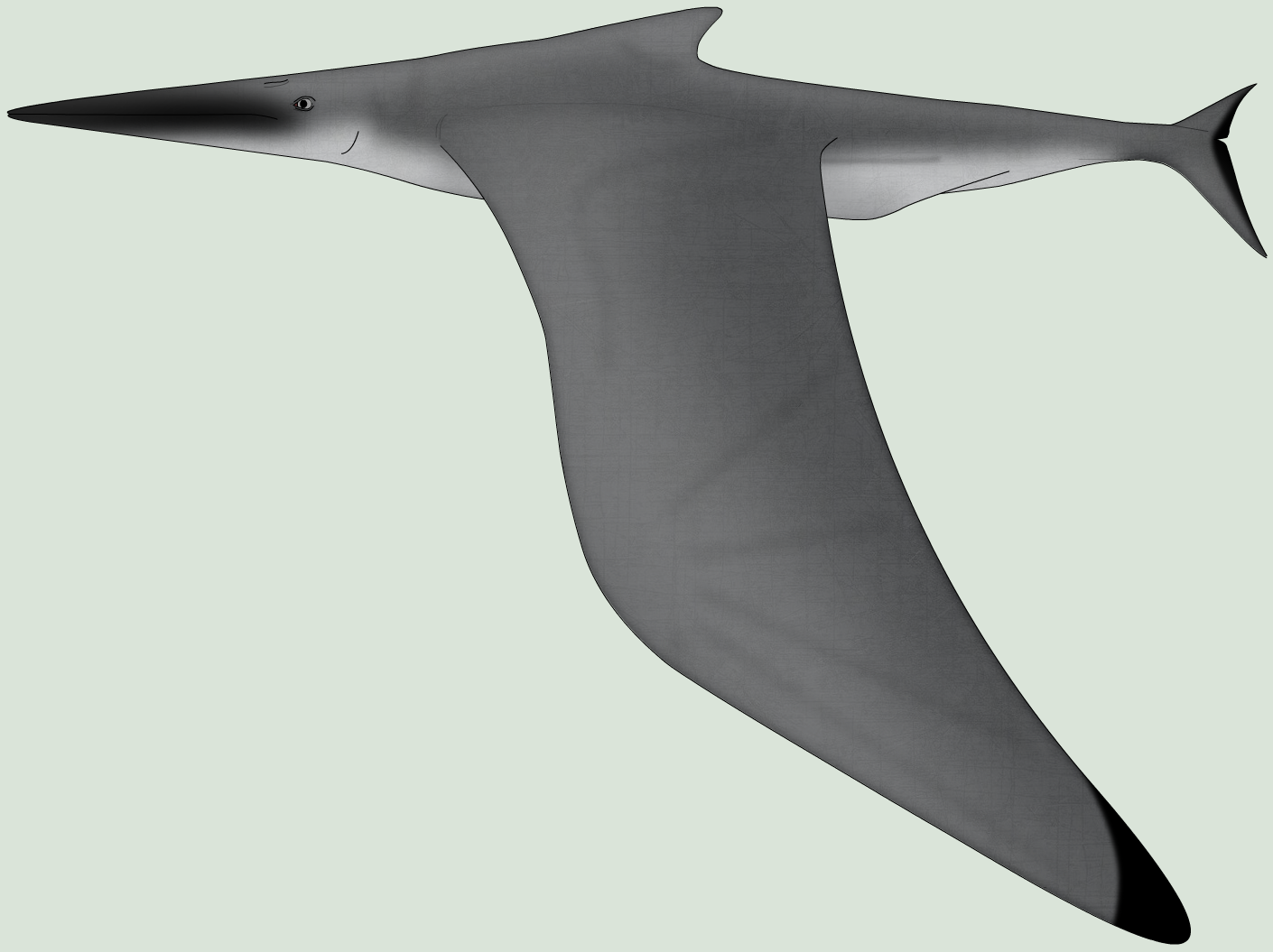

36 million years from now, humanity's descendants on Anthropomundus would have sooner or later discovered (rediscovered?) flight. This time, this discovery was made organically―literally, in the form of true powered flight, only these look nothing like Abbas ibn Firnas or the Wright brothers. Descended from cetanthropichthyans who expanded the surface area of their pectoral flippers to glide above water to attempt escape from predation akin to Terran flying fish, pteranthropids take off by flapping vigorously (or utilizing updrafts for less work) while kicking the water's surface with their flukes, which double as stabilizers as they glide high above the ocean additionally aided by two flaps of taut skin at the pelvic region, then diving at manchovies or other baitmen tracked by superior―if monochromatic―vision by folding their wings inward. Even as fliers, they are still effective swimmers. In fact, they start their lives fully aquatic, precociously swimming catching prey akin to other small cetanthropichthyans and resurfacing when needed, being secondarily pulmonate from having lungs adapted as swim bladders, exhaling from their gill slits. So successful pteranthropids were that even flightless or purely aquatic forms are beginning to pepper the seas and shores around the planet. What will the future hold for these posthumans as the continents become greener and more hospitable?

Well, as the success of the oceanic wingman and other species would indicate, there is much promise for these incipient rulers of the sky.

Among the most common flyers over the oceans of Anthropomundus, the oceanic wingman spies the movements of manchovies from far above before divebombing to catch its quarry. It also swims when taking part in baitball hunts in association with other posthuman species and to mate. It gives birth to a single, precocious offspring which lives like other cetanthropichthyans until its wings are large enough to allow it to ascend from the waterline.